Originally published as a “Historicist” column on Torontoist on November 12, 2011.

Family reads Armistice Day headlines, November 11, 1918. Pictured left to right: Mrs. J. Fraser, Jos. Fraser Jr., Miss Ethel James, Frank James, and Norman James. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 892.

2:50 a.m., November 11, 1918, the office of the Telegram newspaper on Melinda Street. An early morning full of anticipation as workers there and at Toronto’s five other daily newspapers waited for word sometime during the day that an armistice ending the First World War would be signed.

The news during the night had indicated that nothing was expected to happen till this morning. But there was not let up in the eternal vigilance that is the price of efficiency. Jimmie Nicol, the Canadian Press operator, was eating his lunch and joining in the desultory conversation with one ear turned to the key. He had heard the declaration of war flashed into the office and had waited four years and three months to hear this click of the instrument that would tell that the slaughter had ceased. Suddenly he stopped in the middle of a bite and jumped to the wire. Then that crowd of weary waiters came to life as it electrified. Each man knew his work and did it.

Within 20 minutes of the wire notice, special editions of the Telegram and the other papers hit the streets of the city, ready for citizens roused from their slumber by church bells, fire sirens, factory whistles and other loud noisemakers. The war was over and, as the News noted, “Toronto went mad with glory.”

The News, November 11, 1918.

The city needed to let loose after a recent spell of bad news. The influenza pandemic that ravaged the world hit Toronto hard in October 1918. Companies like Bell Telephone lost up to a quarter of their staff due to illness or care giving. Churches, entertainment facilities, libraries, and schools were closed, public gatherings were curtailed, and visitors were not allowed in hospitals. During the pandemic’s peak in mid-October, an average of 50 people a day succumbed to the flu, which ultimately killed around 1,300 Torontonians that month. Combine this with daily reports of the mounting casualties during the final month of battle in Europe and it’s easy to see how Toronto was ready to party.

The Telegram, November 12, 1918.

News of the armistice spread quickly throughout the city. In the east end, residents along Bain Avenue were awakened around 3:40 a.m. by a trumpeter. Half-a-dozen windows opened and an equal number of heads stuck out, asking each other what was going on. “The armistice is signed,” somebody shouted. “The war is over—no fake this time!” Within 10 minutes, most homes in South Riverdale were lit up and pyjama-clad neighbours congratulated each other on the good news. By 4 a.m., as the News reported, “the streets, as a rule deserted and silent at the hour of coming dawn, were filled with quick-marshalled companies of girls and boys, all marching with waving flags and all equipped for carnival.” Traffic jams of cars formed as some revellers decided to head downtown.

The Telegram sent a car around the city to survey how celebrations were breaking out. Everywhere they found scenes similar to those in South Riverdale: people on the streets dancing, singing, playing musical instruments, clanging tin cans, and gathering in their nightclothes and raincoats around impromptu sidewalk bonfires. Streetcars were so packed that passengers sat on the roof.

Streetcar on Spadina Crescent, November 11, 1918. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 7110.

By dawn, streetcar service, apart from a few suburban routes, ground to a halt as conductors and operators abandoned their vehicles to join the festivities. Any driver who attempted to continue to head into the city was met with opposition by their fellow employees, as one determined Queen streetcar operator learned. Shortly after setting out on an eastbound course from Roncesvalles, he encountered a procession of 100 fellow Toronto Railway Company workers led by a Highland piper. When he failed to stop, the procession pulled off the streetcar’s pole and smashed its windows. Without streetcars, people wishing to head downtown jumped onto any automobile—the Telegram reported seeing as many as 28 people sitting in and hanging off one car.

Work was hardly on anyone’s mind that day. Few went to the office, and those who did didn’t stay long. City workers were told to take the day off. Bankers were obliged to stay on the job, but the only ticker tape flowing out of most financial institutions headed out windows onto the streets below. Courts were in session, but Police Magistrate Rupert Kingsford gave clemency to anyone up on charges of drunkenness, gambling, speeding, or other minor offences. “This is not a day for punishment,” Kingsford told those assembled in police court. “It is a day for amnesty and pardon.”

Girl celebrating Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 905.

Out in the streets, a carnival atmosphere prevailed. People draped in Red Ensigns, Union Jacks, and other Allied flags were among those who descended by the thousands onto Yonge Street and other crowded downtown arteries. Some descriptions paint a scene similar to Church Street on Halloween with revellers, in the words of the Mail and Empire, “bedecked themselves in the most grotesque costumes with false and painted faces.” One person dressed as the recently-abdicated German emperor wore a sign which read “I am the Kaiser, kick me.” Knowing people might deliver four years of pent-up frustration against him, the man padded his posterior to soften any swift kicks. Hopefully he wasn’t mistaken for the numerous effigies of the Kaiser burned with glee across the city.

Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 891.

Celebrants along Yonge Street between Shuter and King found themselves in a war zone. The Mail and Empire reported that “for several hours the main thoroughfare presented the appearance of a region that had been subjected to a gas attack, because of the battle of talcum powder by the boys and girls who waged it with little relaxation.” Anyone who objected to being doused in powder was, with the approval of bystanders, showered with a double dose. Despite a few people who were hit square in the eye, people were generally amused by the battle or rolled with it. They had little choice—according to the News: “the crowds were so dense that escape was impossible, and the victims soon purchased and used supplies of their own.” Police directing traffic took the powder showers in stride, even if they “looked more like millers than officers of the law.”

Float representing “In Flanders Field” at Victory Loan Parade, November 11, 1918. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1583, Item 161.

Officially sanctioned ceremonies began at noon on the steps of City Hall (now Old City Hall), where Mayor Tommy Church issued a proclamation. Following that was a previously scheduled Victory Loan parade that became a general celebration. Over 200,000 lined the route along University, Queen, Simcoe, King, Jarvis, Carlton, and College to watch the procession of soldiers and bond-promoting floats. Wounded hospital patients were chauffeured in automobiles. Airplanes dropped pamphlets urging spectators to “lend” to the loan drive. Music was provided by groups ranging from ragtag marching bands to the United States Navy Band led by, in possibly his only personal appearance in Toronto, John Philip Sousa. Of the floats, the most poignant was a tribute to the poem “In Flanders Fields.” The women’s page of the News described the scene portrayed: “There was the grass of the fields, the vivid scarlet poppies and the charred crosses of the men who had fallen. A man in khaki standing looking down at the crosses carried out the picture in its last detail.” When the parade returned to its starting point at Queen’s Park, it was followed by a religious service.

John Philip Sousa, University Avenue, November 11, 1918. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 2576.

The partying continued well into the night. Sousa conducted a concert at Queen’s Park. Dances were held at the King Edward Hotel and other venues across the city. Bonfires burned on, including a large one fuelled by old wagons across from the Albert Britnell bookstore at Yonge and Bloor. A parade through Chinatown (then centred around Dundas and Elizabeth) saw a truck carrying smiling deities wielding gongs. The Star, then based on King Street, ran movies and bulletins on the side of a neighbouring building. Amid the jovial spirit, the News noted that some members of the crowd remembered the costs of the battle just ended: “Mingling with the wild abandon of youthful rejoicing was the note of sadness among those who recalled all too vividly the poignant sacrifice of war, and here and there in the swirling, gleeful crowds were lonely individuals who looked at the people but saw a grave in Flanders.”

The next day, tired Torontonians dragged themselves back to work and settled back into routine. The city estimated clean-up would cost $1,000. Little damage was done, and few arrests were made during the celebrations (it seemed even pickpockets had taken the day off). As the week unfolded, the Victory Loan drive wrapped up and the first postwar contingents of veterans returned home. The uncertainties of what peacetime would hold were pushed aside as the afterglow of the armistice celebrations lingered on.

Additional material from Our Glory and Our Grief: Torontonians and the Great War by Ian Hugh Maclean Miller (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002) and the following newspapers: the November 12, 1918 edition of the Globe; the November 12, 1918 edition of the Mail and Empire; the November 11, 1918 and November 12, 1918 editions of the News; the November 12, 1918 edition of the Toronto Star; and the November 11, 1918 edition of the Telegram.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

This subject was also covered in an earlier installment of Vintage Toronto Ads, originally published on November 11, 2008.

The Globe, November 11, 1918.

November 11, 1918: eager Torontonians, having seen several days of stories in the local dailies that the end of World War I was imminent, waited for word from Europe of the armistice that would bring loved ones home. The newspapers stayed close to their wires to put the presses into motion once the armistice was official. The Telegram described the wait:

The news during the night had indicated that nothing was expected to happen till this morning. But there was not let up in the eternal vigilance that is the price of efficiency. Jimmie Nicol, the Canadian Press operator, was eating his lunch and joining in the desultory conversation with one ear turned to the key. He had heard the declaration of war flashed into the office and had waited four years and three months to hear this click of the instrument that would tell that the slaughter had ceased. Suddenly he stopped in the middle of a bite and jumped to the wire. Then that crowd of weary waiters came to life as it electrified. Each man knew his work and did it.

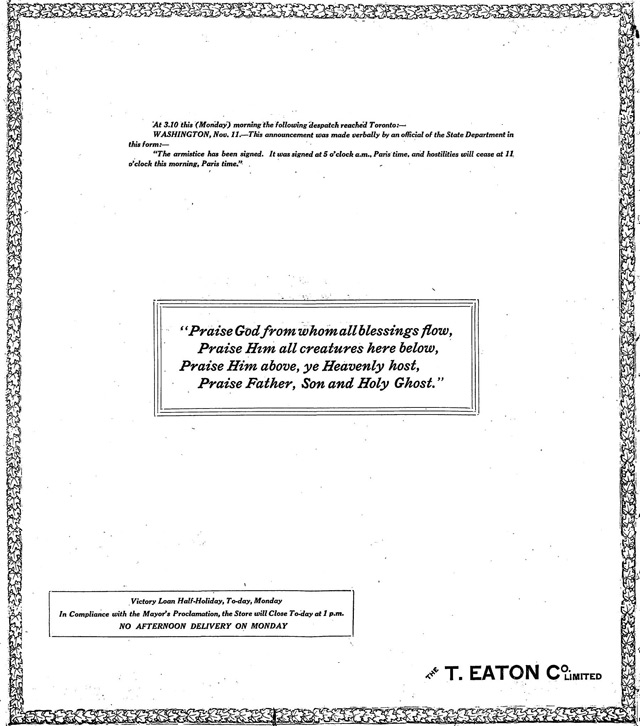

Nicol received the wire at 2:50 a.m. The first edition of the Telegram hit the streets 20 minutes later. The paper used their speediness to take a potshot at the Star, who, “first in fake but last in reliability, put in a tardy appearance with the same news, accompanied by the morning papers.” Eaton’s used their regular advertising space to publish the official announcement and a blessing.

Toronto Star, November 11, 1918.

O’Keefe’s ad may have appealed to one group who welcomed the armistice, local drunks. The Telegram reported that inebriates around the city were “happy as larks” that not only was the war over, but that the city magistrate had declared a one-day amnesty on charges of public drunkenness, gambling, speeding, and other minor offences. The magistrate’s explanation for his actions? “We are doing it for our country.”

Toronto Star, November 11, 1918.

Though the war was over, ads for Victory Bonds were published that day. Pitches soon switched from helping Canadians fight on to aiding returning soldiers and the citizens of countries devastated by the conflict. The city declared a half-day holiday for a bond drive, which quickly turned into a general celebration.

Additional material from the November 11, 1918 edition of the Telegram.

2 thoughts on “The War is Over”