As the James Bond film series marks its 60th anniversary this year, my wife and I are doing a marathon viewing of all of the Bond flicks, providing an excuse for a series of posts on the movies and Toronto: how they were covered, how they were promoted, where they played, and other related stuff.

Evening Standard, October 4, 1962.

While the first official Bond movie, Dr. No, debuted in British cinemas in October 1962, Torontonians, along with much of North America, had to wait awhile before getting their first big screen glimpse of 007 thanks to an eight-month long lag in release dates.

Daily Telegraph, October 6, 1962.

The People, October 7, 1962.

The Guardian, October 8, 1962.

A trio of opening reviews from the London press.

The week Dr. No opened in Great Britain, writer Hugh MacLennan discussed Fleming’s Bond novels in his “A Writer’s Diary” column for the Toronto Star Syndicate. Here’s how he summed up the literary version of Bond.

For Bond, though he is not a bounder, is unquestionably a cad…He uses with relish every dirty trick in the book from the trained edge of his hand against the Adam’s apple to a harpoon shot into the back of a half-naked man surprising on a springboard. He drinks and swears hard, and every woman between 17 and 25, providing she is slim and not a virgin—the latter point is superfluous because he does not believe virgins exist any more—is his natural prey. Moreover, he leaves them to their fate after he has enjoyed them.

Showcase #43, cover dated March-April 1963. Art by Bob Brown.

Comic book readers received an early glimpse of the movie when Showcase #43 hit newsstands in January 1963. The adaptation was originally published in the UK as part of the Classics Illustrated series, but the American edition wound up with DC Comics. They slotted it in Showcase, an anthology series that over the course of its original 93-issue run from 1956 to 1970 introduced readers to the “Silver Age” versions of the Flash, Green Lantern and the Atom, along with heroes such as the Challengers of the Unknown, Space Ranger, Adam Strange, Rip Hunter, Metal Men, Creeper, Hawk and the Dove, and Bat Lash.

Inside front cover of Showcase #43.

Flipping through the adaptation, what sticks out is the colouring of all black characters as Caucasians. I suspect this was done to satisfy distributors and retailers in the southern US.

Artist Norman Nodel muted the iconic introduction of Ursula Andress coming out of the sea, which was probably far too racy for the educational-minded editors of Classics Illustrated. Nodel’s take is too blandly photorealistic – it would have been interesting if DC had decided to do the adaptation in-house with one of their top regular artists (I’m imagining a gritty Joe Kubert take, an adventurous Alex Toth rendition, or plenty of Gil Kane nostril shots).

Toronto Star, June 25, 1963.

Dr. No made its Toronto debut on June 27, 1963 at Loew’s Yonge Street, a complex which marked its 50th anniversary that year. Today the site is the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatre Centre.

The first title sequence by Maurice Binder. Several elements that will stay throughout the series are already in place: the gun barrel, the silhouettes of women, the presence of Bernard Lee as M and Lois Maxwell as Moneypenny in the credits (I’ll cover Lois Maxwell’s Toronto connections in a future post).

Globe and Mail, June 22, 1963.

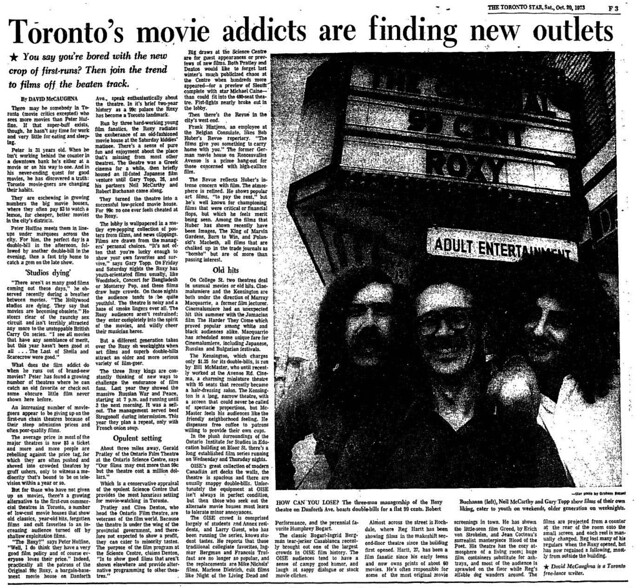

Review by David Cobb, Toronto Star, June 29, 1963.

We enjoyed Dr. No as a first step, but couldn’t resist doing some Mystery Science Theatre 3000 style riffing at certain moments, mainly during Jack Lord’s first few appearances as Felix Leiter…

…which involved humming the Hawaii Five-O theme (which was only six years away for Lord) and making “Book ’em Dano” jokes.

Toronto Star, June 27, 1963.

For its Toronto opening, Dr. No was accompanied by two vintage Tom and Jerry cartoons. Puss Gets the Boot (1940) was the pair’s debut, though they didn’t receive their names until their second appearance. Here’s Leonard Maltin’s description of their initial appearance.

Tom (or Jasper, as he’s called here) is mangy, moon-faced, and designed with a plethora of drawing details (no less than three eyebrows, for instance)., He’s convincingly real as he chases after the mouse, harassing his prey with undisguised delight—and equally credible when he cowers in fear, certain that the smashing of a vase or dish is going to get him kicked outside. The mouse bears a strong resemblance to the later Jerry, although this one is skinnier and more angular than the cuter version that evolved. However, he already possesses the range of expression—registering everything from mischievous glee to cocky pride—that made him so endearing. There is no dialogue between the cat and mouse, and none is necessary. The situations establish their adversary relationship, and the animation pinpoints their character traits.

The other cartoon, 1942’s Fine Feathered Friend, saw the pair engage in henhouse hijinks.

Why would cartoons over 20 years old be paired with a potential blockbuster? United Artists, which distributed Dr. No, had no connection to any theatrical cartoon studio at that point, and would not until it began releasing DePatie-Freleng’s Pink Panther series in 1964. MGM (which had once been owned by Loew’s Inc.) closed its cartoon studio in 1957 but tested the waters for a Tom and Jerry revival via 13 shorts produced in Czechoslovakia by American director Gene Deitch in 1961 and 1962. Despite the obvious low budgets of the Deitch shorts, they were popular enough for MGM to hire Warner Brothers veteran Chuck Jones to produced a new series, which reached theatres with Pent-House Mouse in July 1963.

Toronto Star, June 27, 1963.

The major blockbuster opening that week in Toronto was Cleopatra at the University on Bloor Street. The uncredited writer sounds disappointment people weren’t tying up traffic or acting like screaming teens to get a good view of VIPs like recently retired Broadview MP/former Diefenbaker cabinet minister George Hees.

The prediction that Cleopatra would run two years didn’t hold up. A quick scan of the January 4, 1965 Star shows it wasn’t playing at any of the listed first- and second-run theatres, even though other films released around the same time in 1963 (such as Donovan’s Reef and The List of Adrian Messenger) were still kicking around.

Toronto Star, June 29, 1963.

The following week saw another legendary film make its premiere: The Great Escape.

Additional sources: Of Mice and Magic by Leonard Maltin (New York: Plume, 1987); and the October 6, 1962 edition of the Calgary Herald.