Part One: Advertising the ’67 Ex

Originally published on Torontoist as “Vintage Toronto Ads: Ex 67” on August 31, 2010.

Globe and Mail, August 8, 1967.

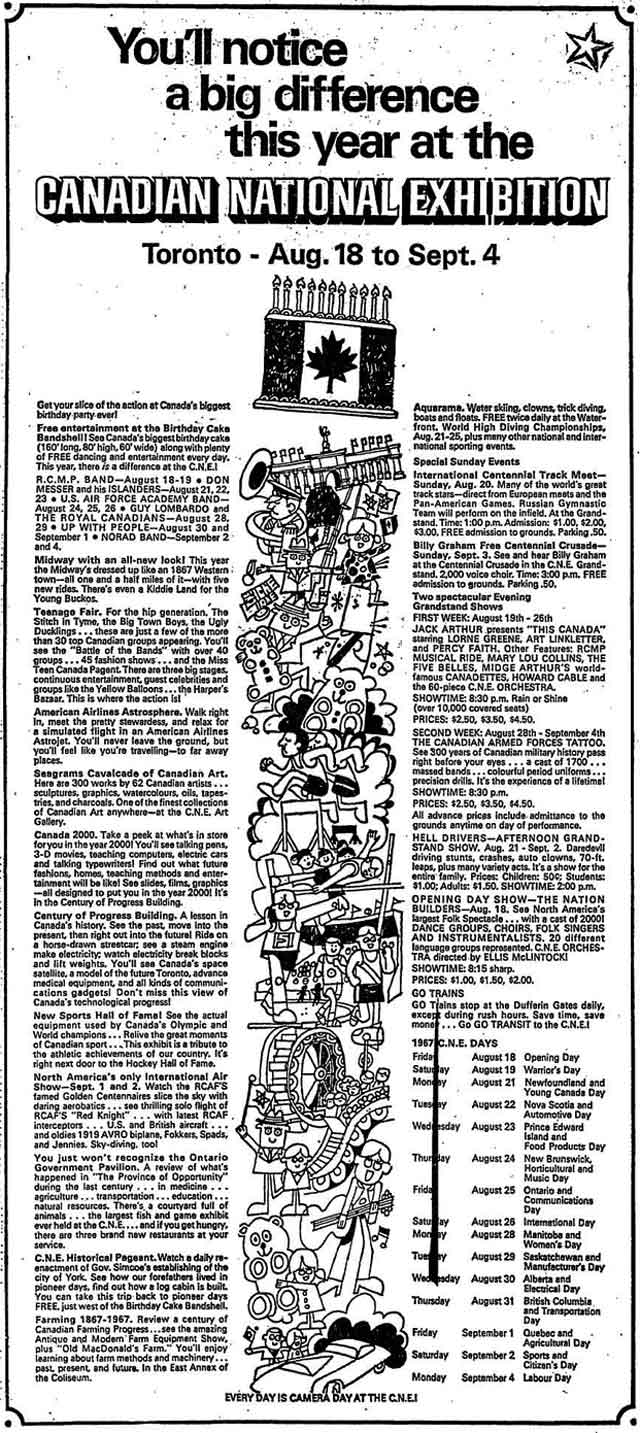

The 1967 edition of the Canadian National Exhibition was not going to be an easy one to market to the public. How could it compete with the once-in-a-lifetime hoopla surrounding the year’s main celebration of Canada’s centennial, Expo 67? Would a trio of entertainers with Canadian roots help?

While the CNE rolled on with its traditional attractions in 1967, City officials who visited Montreal realized changes needed to be made for future editions of the CNE to make it feel less dowdy. Controller Fred Beavis proposed that beer and liquor sales should be allowed, while Mayor William Dennison pondered loosening restrictions that prevented the fair from opening on Sundays. In an editorial, the Star noted that these would be minor changes compared to what it felt the Ex really needed: a major freshening up and the creation of a greater sense of awe and wonder like that experienced at Expo 67 to bring it into the modern age.

It has settled into a rut, with no substantial change for generations. The visitor who goes through the gates each year knows in advance pretty much what he will see. There will be the same dull, unchanging buildings; the same masses of goods for sale—making some pavilions look like second-rate department stores; the same miles of booths with junky merchandise and dubious gambling games; the same bellowing pitchmen. There are, of course, better things than this at the “Ex” every year—but they are smothered in a sea of shoddy carnival gimmicks. This sort of thing may have been good enough 60 years ago, and indeed the CNE has a certain nostalgic charm for many people because it is so old-fashioned. But the CNE has no future as a big city country fair. That is not the way to attract younger people—especially when so many of them have seen “Expo” and know what a fair can be.

The paper recommended that older buildings be gradually replaced by modern structures that could be easily modified for different purposes, that the fair promote national artistic competitions, and do away with the “junk booths and ‘gyp’ shows” (conversely, a Globe and Mail editorial stated that, in a year where Charles DeGaulle gave fuel to separatist sentiments during his visit to Expo, “we should be thankful, in this shattering season, for something familiar and temperate”).

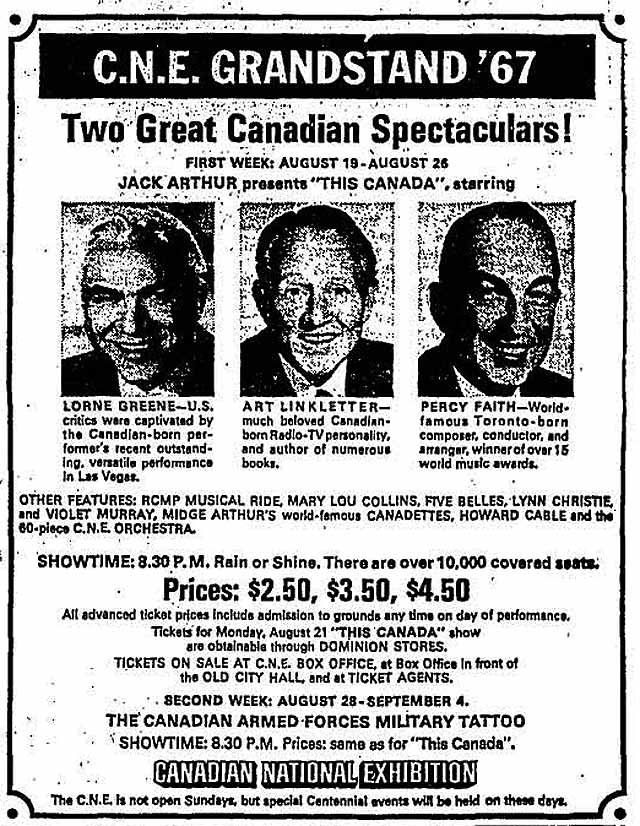

Globe and Mail, August 14, 1967.

For the 1967 Grandstand spectacular, fair officials brought in three expats as headliners: Bonanza patriarch Lorne Greene, daytime variety show host Art Linkletter, and easy listening music maestro Percy Faith. This did not sit well with Globe and Mail columnist Dennis Braithwaite, who hoped any future reforms to the fair would eliminate “spurious Canadianism” as represented by importing talent that was more popular at the time south of the border. Braithwaite didn’t blame Grandstand programmer Jack Arthur, who had brought many popular performers from elsewhere in previous years despite being urged to use homegrown talent.

An invitation from Lorne Greene to visit the CNE in 1967. CNE Archives.

Greene, the one-time “voice of doom” for CBC, was recruited to help pitch the fair in a spot that is among the films placed onto YouTube by the CNE Archives.

Globe and Mail reviewer Blaik Kirby found Greene one of the highlights of a disjointed evening at the Grandstand. Despite one too many jokes about Bonanza, Greene proved to be “a first-class singer and an adept, relaxed comedian” who electrified the audience when he arrived onstage atop a white charger. As for the other headliners, Kirby felt Faith was engaging in his understated conducting of the CNE orchestra (even if the material was overly schmaltzy), while Linkletter was criticized for spewing “the worst of daytime audience participation TV fare onto the CNE stage.” To Kirby, the biggest mistake of the show was allowing the RCMP Musical Ride to be its finale, as the horses were kept too far away from the audience and showcased at too late an hour (after 11 p.m.).

Despite a sluggish start, attendance increased by 31,000 over 1966 to help break the three million visit mark for only the third time in the fair’s history.

Additional material from the July 31, 1967, August 14, 1967, August 21, 1967, September 5, 1967 editions of the Globe and Mail, and the August 2, 1967 edition of the Toronto Star.

Part Two: Moving, Grooving, and Redesigning the CNE

Originally published on Torontoist on August 19, 2011.

Architect Harvey Cowan takes the CNE for a stroll. The Telegram, August 5, 1967.

Amid the lines starting today for doughnut cheeseburgers and deep-fried cola at this year’s Canadian National Exhibition, you might hear an eternal argument: is the CNE a charming anachronism that has provided generations of Torontonians a final taste of summer fun, or an outdated relic that has little reason to continue?

Back in 1967, compared to the stylish, imaginative concepts on display at Montreal’s Expo 67, the CNE seemed so old-fashioned that it prompted one local media outlet to survey Toronto-based architects, designers, and filmmakers involved with Expo: how would they revitalize the old fair two weeks before it opened?

Flipping through the articles about the CNE in the August 5, 1967, edition of the Telegram, it’s clear both writers and interviewees weren’t impressed with the current state of the fair. Nearly all felt the CNE was a tatty, lowbrow, Victorian-era embarrassment lacking a compelling vision for the future. As architect Robert Fairfield (who designed the Festival Theatre in Stratford) noted, the CNE “failed to enter the 20th century, by clinging to the idea that it’s an institution. Like a beloved friend, it has been allowed to grow old, sentimental, eccentric, and untidy.” One major problem was finding solid financing to allow for innovative and interactive exhibits, especially from large industrial sponsors. Another issue was how to better utilize the grounds during the other 50 weeks of the year, with ideas ranging from a longer summer schedule of concerts and events to year-long exhibits. Restaurant designer Chet Borst proposed turning the grounds into a year-round restaurant district with eateries at all price ranges offering menus that represented all regions of Canada and themed after different Ontario cities or time periods (a rough-and-tumble bar from Windsor, a stately government house from Ottawa, a futuristic cocktail lounge, etc.).

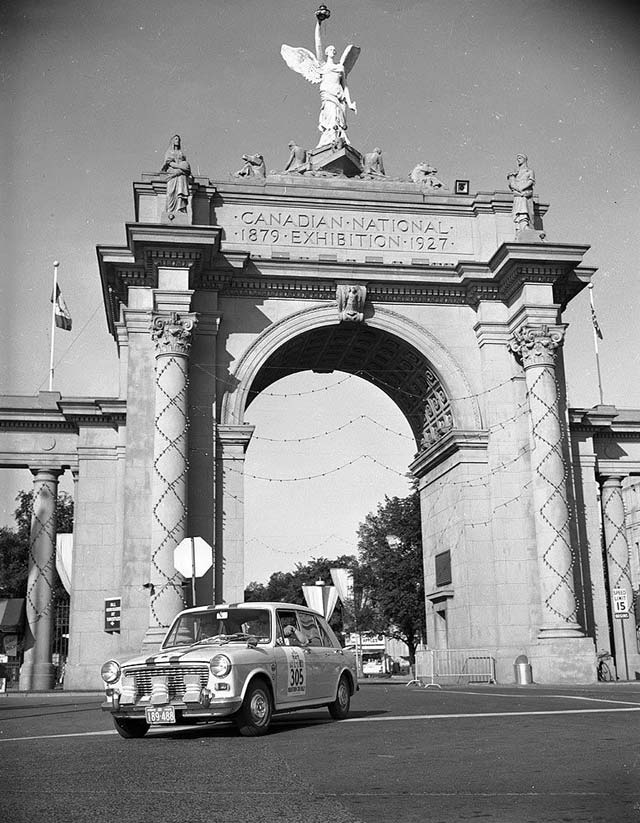

Had several of those interviewed by the Telegram had their way, the Princes’ Gates would not be greeting visitors this year. Car 305, leaving CNE grounds via Princes’ Gates, at start of CNE’s first marathon car rally, 1965. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 5802.

For designer/Marshall McLuhan associate Dr. Daniel Cappon, the CNE should have moved forward as a national fair like Expo, not a northern version of Coney Island. “Use the psychedelic stuff of Expo, the participating stuff, and not just be passive and visual,” noted Cappon. “Involve the public in half an hour of playing soccer. Involve them with sculpture, with music. Install IBM machines, ask the people a lot of questions, get them involved in the answers. Let them know we’re interested in how they react.” Other suggestions from the interviewees ranged from tearing down the viewed-as-a-boring-gateway Princes’ Gates (which we think is one of the site’s highlights) to building internal transportation systems like monorails. One of the few people to admit liking the CNE was industrial designer Morley Markson, who enjoyed the energy of the midway and its pitchmen and wished the displays captured that excitement.

The Telegram also asked architect Harvey Cowan to write a two-page spread on what was wrong with the CNE (which he compared to an old lady on its deathbed) and how he would fix it. High among the liabilities: dismal streetcar stops that should have been sold to the nearby Canada Packers plant. “It should be inherent to the design of an arrival station that the space says ‘Welcome,’” Cowan noted. “The CNE stations say ‘Go home, who needs it.’” Cowan also found the existing buildings an aesthetic mishmash, the displays dull, the central location of the midway a bottleneck, the entrances mundane, and the formal restaurants displaying “all the gaiety and excitement of open house at the City Morgue.”

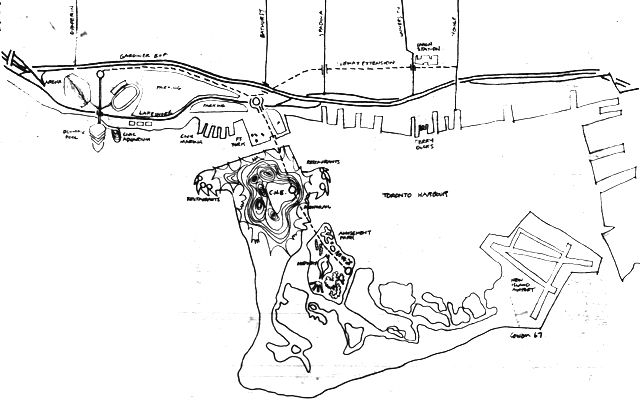

Map of architect Harvey Cowan’s vision for improving the CNE. The Telegram, August 5, 1967.

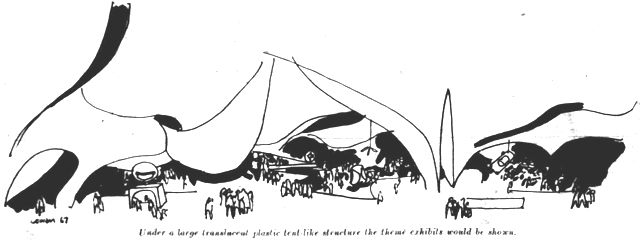

So how would have Cowan improved it? Via various methods that, had they come anywhere near reality, would have dramatically altered the western waterfront and made a few people unhappy. Cowan’s vision saw the demolition of all buildings at Exhibition Place except for the Grandstand. Their replacements would have included terraced, well-landscaped parking garages, a domed stadium, and a sports centre. Down by the water, an aquarium and Olympic pool would rise. Fort York would have been moved to the shore by the Western Gap, with a public marina beside it. Existing yacht clubs would have been relocated further west along the shoreline. Over on the Toronto Islands, Cowan envisioned the airport moved, with the help of infill, to what would have no longer been Algonquin and Ward’s Islands (at the time, Metro Toronto was determined to remove the remaining residents). The airport’s former location would become the main exhibition area, covered in a plastic, tent-like structure similar to the Ontario pavilion at Expo 67. The midway would have found a new home on Muggs Island. To handle visitors, the Yonge subway line would have extended along the railway lines to the new mainland sports facilities, with a stop at the foot of Bathurst that connected to a monorail service to the islands.

A design proposal for the main exhibition space on the Toronto Islands. The Telegram, August 5, 1967.

Some suggestions in the Telegram articles may have lingered in the minds of CNE officials. A master plan approved in 1971 called for the demolition of 12 major buildings to make way for new facilities for trade shows and conventions, though only a few, like the Shell Tower, were torn down. While the same year saw Ontario Premier William Davis announce provincial funding for a monorail or other public transit link between Union Station and the CNE, a permanent link didn’t exist until the Harbourfront streetcar line reached the grounds in 2000. Design ideas from Expo 67 were utilized for an exhibition and entertainment space close to the CNE grounds but not part of it: Ontario Place.

Despite the criticisms aimed at the CNE during 1967, the fair broke the three million visit mark for only the third time in its history. Though attendance has dropped to an average of around 1.3 million visitors per year over the past decade, and the fair now relies on gimmicks like novelty caloric nightmares to draw customers, something wouldn’t be right if the CNE wasn’t around as a nostalgic link to Toronto’s past or to argue about the quality of over time.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

The Telegram, August 5, 1967.

After presenting its articles speculating on the CNE’s future, the Telegram presented a traditional preview of that year’s fair.

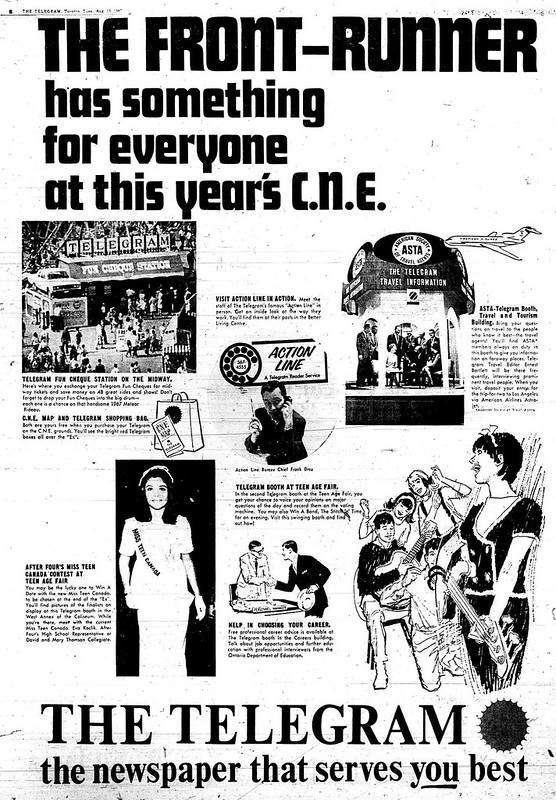

The Telegram, August 15, 1967.

The Telegram also offered its own attractions at the fair, including tie-ins to its popular “Action Line” service and “After Four” teen section.