Earlier this week, Torontoist reported that Councillor Doug Ford (Ward 2, Etobicoke North) was dismayed because he perceived there to be more library branches in his area of Etobicoke than Tim Hortons. Though the actual numbers don’t support Mr. Ford’s claim, would it be horrible if it was true? Through collections and outreach programs, the Toronto Public Library’s 99 branches provide more brain food than all of the double-doubles and boxes of Timbits sold throughout the city.

Yet curtailing access to the library, through reduced hours or branch closures, is among the recommendations KPMG provided in today’s portion of the Core Services Review. Based on past experience, attempts to implement such advice, to force reduced hours or closures onto local libraries, will be met with stiff opposition, and politicians will either back down or tone down the degree of service reduction.

Though a limited form of library via the Toronto Mechanics’ Institute was available as far back as 1830, it wasn’t until the early 1880s that city officials seriously set out to to create a free public library. Championed by Alderman John Hallam, a bylaw to create a public library was placed on the January 1, 1883, municipal ballot. Detractors argued that books were so plentiful and cheap that there was little reason for taxpayers to fund a library. That argument was countered in many newspaper editorials: “We wonder,” wrote the Mail on Christmas Day, 1882, “if those who say so ever put themselves in the artisan’s place, and calculated how much he could spare in a year, after supporting his family, for books. For a quarter of a dollar in taxes, or less, the library will give him use of, or choice from, thousands of volumes.” The bylaw passed by a landslide.

After a brief search for sites, the Mechanics’ Institute agreed to turn over its collection and property. Following renovations, the TPL officially opened its doors at the northeast corner of Church and Adelaide streets on March 6, 1884. Though it quickly became popular, critics felt the collection contained too much mind-corrupting fiction and needed more dry reference works. Hallam noted that he learned far more from the likes of Charlotte Brontë, Charles Dickens, and Sir Walter Scott than nine-tenths of the published sermons that Torontonians considered “good” literature.

Those who considered the TPL a passenger on the Victorian equivalent of the gravy train—such as the author of the following verse that appeared as a letter to the editor of the Toronto World—continued to air their beefs in public forums:

What is this building, father?

This, my son, is the celebrated free library.

Why is it called a free library, father?

Because everybody is compelled to subscribe.

What was the origin of it?

Ex-Ald. Hallam’s vanity.

What good is it, father?

To increase the taxes and circulate sensational novels.

What are sensational novels?

Tales where shop-girls marry lords.

What is the use of reading them?

They make people discontented and negligent.

Has the library any other purpose?

Yes, my son, it provides some good fat berths.

Do the subscribers manage it?

Nominally they do, but really they do not.

Who does, then?

Some people who pay very little towards it.

Is it very popular?

Wait until the tax bills come in.

How are the public benefitted by it?

Ask the trustees, my son.

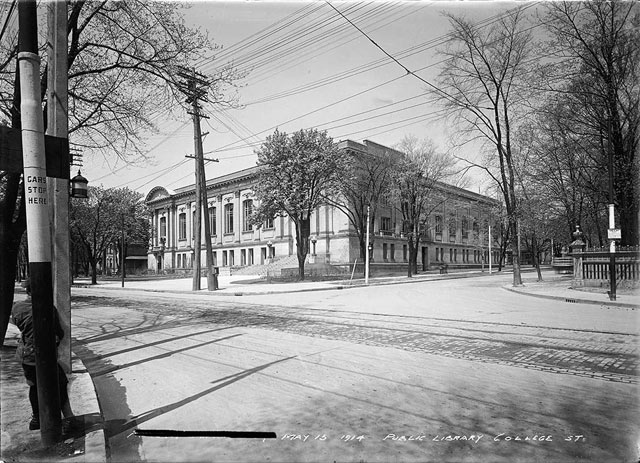

Metropolitan Toronto Central Library, northwest corner of College and St. George streets; the predecessor of the Toronto Reference Library, it was built with Carnegie money. Photo taken May 15, 1914. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1231, Item 307.

For the rest of the 19th century, library officials were frustrated by the city’s refusal to provide the full amount of funding it was allowed under provincial law. Branch closures were frequently threatened but never carried out. City council continued to cut funding until it made one reduction too many in 1900. The library board sued for the lost funds and won. Funding stabilized after that point, thanks largely to Carnegie grants that began a few years later.

After the library systems in Toronto and its suburbs experienced years of growth, threats to services became common from the mid-1980s onward as municipalities attempted to cut costs. The mere threat of a library closure was enough to spur neighbourhood activists into action—among the small branches frequently used for target practice were Mount Pleasant, Queen-Saulter, Silverthorn, Swansea, and Todmorden. The Toronto Reference Library (and its predecessor, the Metro Reference Library) incurred reduced hours and closures for a week at a time during the late 1990s. Mayor Ford’s favourite branch, Urban Affairs, was recommended for closure in 1996 in anticipation of cuts.

Perhaps the most decimated branch was City Hall, which was supposed to be scrapped in October 1995 in order to save $640,000. Politicians figured it would be an easy cut, since there wouldn’t be opposition from ratepayer groups as there was in neighbourhoods where other branch closures were announced, and the space could easily be rented out for a restaurant or other commercial uses. Globe and Mail columnist Colin Vaughan pointed out the faultiness of the library board’s argument, which said that most of the branch’s users lived outside pre-amalgamation Toronto:

One reason given for closing the City Hall branch over, say, the less-used Beaches branch was that many of the users are business folk from the suburbs, as opposed to the local residents who frequent neighbourhood libraries. Perish the thought that Toronto should serve as a clearing house for the edification of the barbarian hordes. What next? Bar suburban patrons from attending those free lunch-time concerts in Nathan Phillips Square?

The branch remained open but saw its holdings reduced from 75,000 items to 25,000 and its operating time shrunk from nine-and-a-half to three hours a day.

In September 1999, the post-amalgamation TPL recommended closing 12 branches over the next five years. Of those listed, only one, Niagara, bit the dust. Protest against the proposals was loud, especially for the Mount Pleasant and Swansea branches. Noting that the report that recommended Mount Pleasant’s closure was called “Reinvesting in Our Future,” Councillor Michael Walker snarled, “That sure as heck isn’t reinvesting in any future…This library only opened about 10 years ago. There was a clear shortfall of library services in this neighbourhood then.” Down in Swansea, Councillor David Miller reminded the library board that the branch there was as much a monument to fallen soldiers as a library. “The original collection was donated by the residents of Swansea as a living memorial for 22 boys who didn’t return from World War I,” Miller noted. “It’s just as much a memorial as a statue in a park. I think the city has the same moral and ethical obligation to uphold that memorial.”

As mayor, Miller later saw the library board eliminate Sunday operations at 16 branches in September 2007 in reaction to a city budget crisis that Miller blamed on the deferment of votes on new land transfer and vehicle registration taxes. An arbitrator ruled the following month that the board was wrong to act so quickly, which led Miller critics like Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong (Ward 34, Don Valley East) to gloat over how ineptly the incident was handled. “It was a very cruel decision to force the closures of the library branches, and to see that there are no savings that are going to be accumulated makes it even crueller,” Minnan-Wong told the Star.

But will he have the same reaction if the current council follows KPMG’s recommendation and pushes for library branch closures that will provide, at best, middling savings? Or, if such an event comes to pass, will he tell users of targeted locations that, rather than a cruel blow to their neighbourhood, the loss of a library branch is merely a sacrifice needed to right the financial health of the city? Even if all that happens is a reduction in service hours, we know that defenders of Toronto’s libraries are preparing to protect an institution we should all be proud of.

Additional material from A Century of Service: Toronto Public Library 1883–1983 by Margaret Penman (Toronto: Toronto Public Library Board, 1983), Free Books for All: The Public Library Movement in Ontario 1850–1930 by Lorne Bruce (Toronto: Dundurn, 1994), and the following newspapers: the July 10, 1995 edition of the Globe and Mail; the December 25, 1882 edition of the Mail; the September 21, 1999, September 22, 1999, and October 16, 2007 editions of the Toronto Star; and the January 30, 1884 edition of the Toronto World.

UPDATE

The Ford brothers’ attempts to shrink the Toronto Public Library were met with public backlash, notably from Margaret Atwood. While the in-the-works closure of the Urban Affairs branch at Metro Hall went ahead (which led to confusion in accessing its holdings for years as its collection was integrated into the Toronto Reference Library), the other branches remained open. The TPL expanded in the years that followed, with new branches serving the Fort York neighbourhood and Scarborough Civic Centre.