This post merges several pieces I’ve written about the Gardiner Expressway over the years, along with additional material.

Gardiner Expressway, 1962. The caption was “Ready for ’67 Centenary if weather co-operates.” Photo by Dick Darrell. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0115131f.

Frederick G. Gardiner was proud of the expressway named in his honour. “You know,” he noted in a 1964 interview, “I used to lie in bed dreaming in Technicolor, thinking it was too big. Now I know it isn’t. Maybe in 20 years time, they’ll be cursing me for making it too small. But I won’t be around to worry then. Right now, I’ve come up smelling of Chanel No. 5.”

When Gardiner died in 1983, few liked the scent of his expressway. They cursed him for pushing a crumbling roadway increasingly seen as a barrier between downtown and the waterfront. Decades of city reports have suggested demolishing some or all of the expressway, triggering debates that will turn anyone’s face blue. While its fate eternally hangs in the balance, millions are spent every year to keep it in service. Every time a major reconstruction project occurs that slows down traffic, you’d swear by the tone of the media that Armageddon is descending upon the city.

But there was a time when regional officials believed the Gardiner Expressway would solve bottlenecks plaguing a growing city in the early 1950s. Had it been built to its full extent via the Scarborough Expressway, drivers might have enjoyed views of Humber Bay, the downtown skyline, and the Scarborough Bluffs.

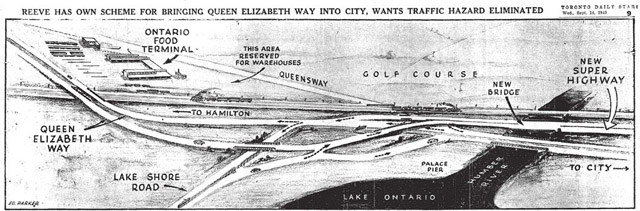

Sketch based on suggestions by Etobicoke Reeve Clive Sinclair on bringing the Queen Elizabeth Way into Toronto. Toronto Star, September 14, 1949.

The combination of the opening of the Queen Elizabeth Way in 1939 and suburban growth had led to frequent traffic jams caused by commuters entering the city along the old Humber Bridge. Visions of a waterfront expressway were included in the city’s 1943 master plan, but it took time for plans to firm up. In 1949, Etobicoke Reeve Clive Sinclair suggested the plan shown here, which he felt would reduce congestion he feared would emerge when the Ontario Food Terminal opened on The Queensway. The key to Sinclair’s plan was cutting the link between The Queensway and the approach to the QEW. “We’ve already had too many pedestrians killed or injured trying to dodge express traffic at this corner,” he told the Star.

Frederick G. Gardiner, taken during a photoshoot for Time magazine, April 5, 1956. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1653, Series 975, File 2262, Item 32745-3.

Enter Frederick Gardiner, chairman of the newly formed regional government of Metropolitan Toronto. As a Toronto Life article noted 40 years later, “Gardiner liked big solutions to big problems, and he brought an entrepreneurial flair to city government. He loved building things, loved to get plans pushed through and get the shovels in the ground.” As Gardiner once observed, “a municipality is no different from an industrial undertaking.” Fixing the bottlenecks at the bottom of the city was right up his alley.

Toronto Star, July 8, 1953.

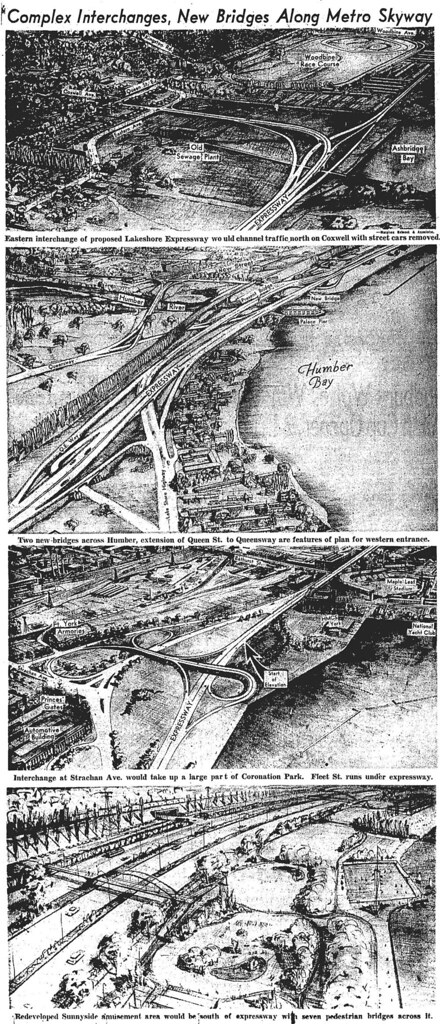

One of Metro’s first acts was to announce in July 1953 that its executive committee had unanimously approved a motion by Gardiner to meet with regional planning authorities to discuss what was soon dubbed the Lakeshore Expressway. The highway would run from the Humber Bridge to Woodbine Avenue. Two sections would be elevated (Humber Bridge to Bathurst Street, and Cherry Street to Woodbine), with surface streets handling the traffic flow through downtown. Toronto Mayor Allan Lamport urged caution with construction—“We can’t go too fast on this. It is absolutely essential.” One of the main questions was which side of the CNE grounds should the expressway be built: on the north side, along the rail corridor, or on the south via fill into the lake?

Toronto Star, January 2, 1954.

As 1954 dawned, Gardiner and Scarborough Reeve Oliver Crockford supported a plan to extend the Lakeshore Expressway east to meet Highway 401 at Highland Creek. The route would have cut through east end neighbourhoods before proceeding along the bottom of the Scarborough Bluffs. Gardiner saw what was later known as the Scarborough Expressway as a solution to potential bottlenecks at Woodbine Avenue and Kingston Road, while Crockford felt it would help halt the erosion of the bluffs. The Scarborough Expressway remained in regional plans for decades before being scrapped.

Toronto Star, May 3, 1954. Note the proposed interchange with Strachan Avenue in the upper right corner, which was never built, which would have provided “access to the north and to local destinations on Fleet Street” (primarily, I suspect, Exhibition Park and Maple Leaf Stadium).

On May 5, 1954, Metro Council received plans for the Lakeshore Expressway. The $49.8 million project would be elevated above Fleet Street (now Lake Shore Boulevard) from Bathurst Street to Cherry Street. To alleviate congestion in the core, a two-level parking facility with direct ramps would be built under the expressway between Yonge Street and Parliament Street.

Globe and Mail, May 4, 1954. Click on image for larger version.

The route would run south of the CNE, and it was predicted the fairgrounds would receive 25 additional acres from the fill required for the expressway.

Globe and Mail, May 4, 1954

A Globe and Mail editorial predicted that the new road “ought to eliminate the worst of the waterfront traffic problems, at least for some years to come.”

Construction of Queen Street West extension, 1955. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 137, Item 13.

Two other road projects were rolled into the Lakeshore Expresseway. In the west end, Queen Street was extended westward to meet up with The Queensway via a new bridge across the Humber.

Construction of Queen Street West extension, 1955. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 137, Item 10.

This stretch, which opened in December 1956, was eventually treated as an eastern extension of The Queensway.

Construction of Woodbine Avenue extension, circa 1955. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 115, Item 15.

In the east end, Keating Street (now Lake Shore Boulevard) was extended from Leslie Street to Woodbine Avenue to provide an eventual end to the expressway. Opened in December 1955, residents soon dubbed the tight curve leading Keating onto Woodbine a “death trap.” Eastbound drivers going 55 miles an hour often found themselves driving into the southbound lanes of Woodbine or climbing onto the northbound sidewalk. Local councillors received complaints from residents ranging from smashed fire hydrants to a car hitting one home’s veranda. Over 60 years later, this curve remains problematic.

Globe and Mail, May 19, 1954.

One east-end vision which never materialize was a plan to build a ramp on the west side of Woodbine Racetrack, which would have connected the Lakeshore Expressway to Kingston Road and Dundas Street East (which was still being stitched together from local side streets).

Empress Crescent, looking east from Dowling Avenue and Lake Shore Boulevard West, 1956. Photo by James Salmon. Toronto Public Library, R-912.

Construction on the Lakeshore Expressway began on April Fools Day 1955, concentrating on the stretch between the Humber and Jameson Avenue. Around 150 homes were demolished to make way for the expressway and its related projects, mostly in south Parkdale around Dowling Avenue and Jameson Avenue. Streets like Empress Crescent vanished from city maps. When the Globe and Mail printed pictures of the rubble left behind by demolitions in 1957, it described the scene as “ruins reminiscent of a Second World War bombing raid.”

Gardiner Expressway, looking west from east of the foot of Roncesvalles Avenue, during construction, showing Lakeshore Road bridge over CNR tracks, south of King Street and Sunnyside Railway Station, July 21, 1957. Photo by James Salmon. Toronto Public Library, R-934.

Construction also brought an end to Sunnyside Amusement Park, which would be revamped as a city beach. The nearby bridge connecting Lakeshore Road (now Lake Shore Boulevard) with the King/Queen/Roncesvalles intersection also met its demise. The Sunnyside train station survived the building of the expressway, but ceased passenger service in 1967.

Parkside Drive, looking north from Lakeshore Road, July 21, 1957. Photo by James Salmon. Toronto Public Library, R-1714.

A new bridge waiting for the Lakeshore Expressway to cross it.

A December 1956 front page story in the Globe and Mail predicted that by 1980 the city’s expressway system (then projected to include the Crosstown, Don Valley Parkway, Lakeshore, and Spadina) would be dominated by buses, as some Metro officials hoped to ease future congestion by banning parking downtown. The idea was that suburban commuters would leave their cars in giant lots next to the expressways, hopping on buses to finish their journey.

Toronto Star, July 2, 1957.

As construction proceeded, there were concerns that the expressway might permanently stop at Jameson Avenue. Metro was having problems convincing higher levels of government to help fund the proposed subway line along Bloor Street. Gardiner believed Metro couldn’t raise enough money to fund its expressway and public transit plans. “You simply cannot provide sufficient highways and parking space to accommodate every person who desires to drive his motor vehicle downtown and back each day,” Gardiner noted in January 1956.”Additional rapid transit is the only answer. It is a snare and a delusion to keep on spending millions of dollars on highways because the province will subsidize them 50 per cent. We know that beyond a certain stage $1 spent on more arterial highways and parking facilities.”

Problem was that Metro council preferred spending money on roads than transit. Eventually, outside funding for the subway came through.

Copy of a cartoon by Bert Grassick published in the Telegram, August 29, 1957. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1567. Series 648, File 26, Item 1.

On July 29, 1957, based on a suggestion from Weston Mayor Harry Clark, the Metro roads committee renamed the Lakeshore Expressway the Frederick G, Gardiner Expressway. Clark felt it was a gesture of appreciation for leading Metro through its formative years. The tribute pleased Gardiner.

Aerial view of the Gardiner Expressway, August 14, 1958. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 37, Item 1.

At 3 p.m. on August 8, 1958, dignitaries including Gardiner, Ontario Premier Leslie Frost, and Toronto Mayor Nathan Phillips officially opened the first section of the expressway, which ran from the Humber to Jameson Avenue. Frost praised Gardiner for his leadership. “Fred, you were the obvious man to do the job.”

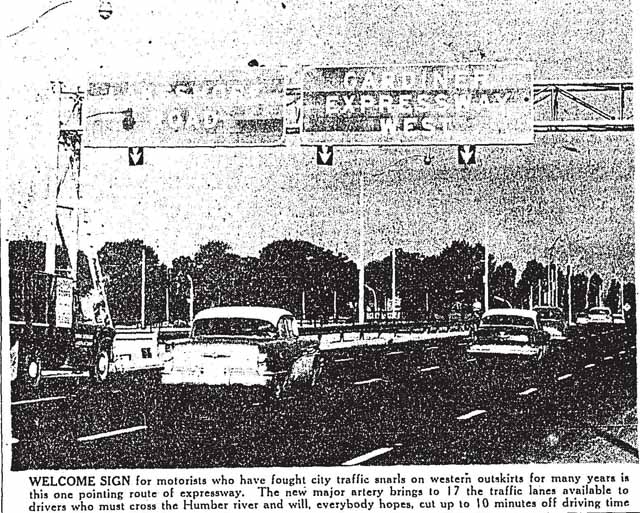

Toronto Star, August 7, 1958. Note optimism about cutting driving time by 10 minutes.

The road experienced its first traffic jam that day, a mile-long backup which would seem mild compared to present-day gridlock. As the Globe and Mail’s Ron Haggart put it, “the traffic jam was the best tribute of the day to the need for the Frederick G, Gardiner Expressway.”

East end of Gardiner Expressway at Jameson Avenue/Dunn Street, 1959. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 58, Item 3.

In an essay in the commemorative book published for Toronto’s 125th anniversary, Toronto ’59, Nathaniel A. Benson placed the Gardiner in the context of the evolution of Toronto’s shoreline.

The lakeshore once was open, save for a staunch little lighthouse and an old-fashioned yacht club. Today there rise the towers of a great Molson brewing plant, the imposing Tip Top Tailors Building, the head offices of Loblaw’s, and the multi-million dollar home of the Toronto Baseball Maple Leafs. The garish lights of the Frederick G. Gardiner Expressway cut spectacularly along the railway tracks, with its day-and-night ceaseless whizz of traffic shaking the peace of the ancient graves in the old military cemetery on Strachan Avenue, grazing the heroic battlements of old Fort York.

Plans considered for Fort York, Toronto Star, October 4, 1958.

After further study, the route of the Gardiner was switched to the north side of the CNE. This placed Fort York in the path of the expressway, which lead to protests throughout 1958 from groups ranging from historical societies the Toronto Women’s Progressive Conservative Association. The tide of voices against proposals to move the fort led to one of Gardiner’s few losses when it came to the expressway.

Construction of the new Dufferin Gate, 1959. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 58, Item 8.

While Fort York was saved, the CNE’s Dufferin Gate wasn’t. Fairgoers passed under the old landmark for the last time in 1957. Two years later, construction was well-underway for its replacement.

Construction of the elevated section of the Gardiner Expressway, 1959. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 37, Item 19.

By the end of the 1950s, some politicians and local media grew impatient with the slow pace of construction, which wasn’t scheduled to end until 1965. “At such a pace,” noted a December 1959 Globe and Mail editorial, “Metro might not bother at all. The growth of traffic will far outstrip the growth of the road, and at the end of 10 years congestion will be worse than when the work was started.” Part of the blame was placed on Frederick Gardiner’s refusal to borrow more than $100 million a year to fund all Metro capital works projects.

Globe and Mail, November 3, 1960.

By the end of 1960, designs were close to being finalized for the expressway’s connection with the Don Valley Parkway. Hopefully Frederick Gardiner and Nathan Phillips didn’t collide into each other. This cartoon also shows the streets (Fleet and Keating) which soon became Lake Shore Boulevard East.

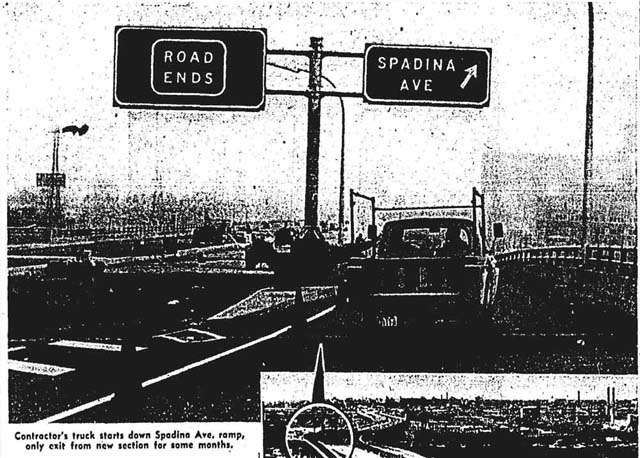

Eastbound Spadina Avenue ramp, Globe and Mail, July 31, 1962.

The Jameson-Spadina section opened during morning rush hour on August 1, 1962. Despite the potential bottleneck at the eastbound Spadina ramp, one travelled noted that his evening rush journey on opening day from the Humber to Spadina and Front took 10 minutes.

Jarvis Street, east side, looking northeast from Lake Shore Boulevard East, showing Gardiner Expressway under construction, 1963. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 5603.

Note the billboards in the far background. The distraction provided by advertising was a growing safety concern, which led Metro’s transportation committee to recommend that no ads be placed within 150 feet of the Gardiner or the Don Valley Parkway.

Lake Shore Boulevard East, looking west from Cherry Street, showing Gardiner Expressway under construction, between 1961 and 1964. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 5619.

John Bentley Mays writing about the Gardiner (in this case, describing wandering underneath the expressway near Fort York):

Few sites more forsaken lie this close to Toronto’s busy, dense downtown mountain-range of glass. Overhead, the wide steel belly of the Gardiner’s traffic level lies like a flat green snake on a series of tall, water-stained concrete brackets. Underneath spreads the expanse of loose gravel, some of it used as a gathering place for trucks, some of it the dusty yard of a factory in which big cement blocks are fabricated.

One hesitates to use the word beautiful of such a forbidding place, though the word fits the hill. There is a strong visual surge and power here: in the dignified rhythms of the expressway’s tapered reinforced-concrete supports, marching away into the distance like an immense Baroque colonnade, in the tough muscularity, in the ensemble of cement factory and rumbling trucks. There is a gruff beauty here that swank towers nearby can’t touch.

Constuction of the Gardiner Expressway, 1964. Photo by Frank Grant. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0115133f.

The caption for this photo reads “Full speed ahead: Workmen are busy levelling the groun underneath the concrete arches which will carry the expressway in the York-Jarvis area. By 1967 the Gardiner is expected to be extended still further to Leslie St.; and by 1972 will stretch out across Scarboro to link with Highway 401.”

Globe and Mail, November 6, 1964.

Besides the link between the Gardiner and the Don Valley Parkway, November 6, 1964 also saw the opening of most of the Eastern Avenue flyover.

Globe and Mail, May 5, 1966.

What proved to be the final stretch of the Gardiner, from the Don Valley Parkway to Leslie Street, was opened on July 15, 1966. Intended to be the first phase of the Scarborough Expressway, it would have intersected with Highway 401 at Highland Creek. Had a request to the Ontario Municipal Board from a citizen group inspired by the fight against the Spadina Expressway not delayed work, the next approved phase of the Scarborough Expressway would have extended it to Birchmount Road and Danforth Road. While Queen’s Park cancelled Spadina in June 1971, provincial officials were willing to fund a short extension of the Scarborough Expressway to Coxwell Avenue if the OMB approved. There was also the matter of purchasing homes (1,000 in the original plan, 500 after a revision) in the path of the projected route.

Photo by Boris Spremo, originally published in the November 21, 1973 edition of the Toronto Star. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0011711f.

The original caption for this photo:

Opponents of the proposed Scarborough Expressway arrive at The Star Forum by bus last night, practising what they preach on the desirability of transit over private cars. Members of action groups left their cars at home and chartered a double-decker bus and one from Toronto transit Commission. They brought signs proclaiming their beliefs but a policeman made them leave them outside.

The “Star Forum” was a session held at the St. Lawrence Centre on November 20, 1973 to discuss whether the Scarborough Expressway should be built. Metro chairman Paul Godfrey indicated he’d support the project based on what he knew up to that point, but wouldn’t commit himself to a position until a Metro report was issued in February 1974. TTC chairman Karl Mallette felt further development of public transit in Scarborough would make the expressway obsolete (if only he knew the battles and delays to come on that front…). “The plain fact is that expressways don’t solve urban transportation problems,” Mallette observed, “they create more of them. They’re becoming prohibitively expensive and are an intolerable intrusion in and near residential areas.”

The next year, Metro Council scrapped further construction.

View of Gardiner Expressway looking west from the CN Tower, between 1976 and 1981. Photo by Ellis Wiley. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 124, File 13, Item 2.

The first cracks in the Gardiner were observed in 1962. Metro roads commissioner George Grant blamed heavy traffic, while the province claimed a thinner-than-normal coat of asphalt was used while building the expressway’s first section. A year after Frederick Gardiner died in 1983, an ongoing repair program began to attack the effects of expansion and contraction on the concrete.

View of Gardiner Expressway looking east from the CN Tower, between 1976 and 1981. Photo by Ellis Wiley. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 124, File 13, Item 13.

Chaired by former mayor David Crombie, The Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront’s 1992 report provided a good summary of the issues many Torontonians have with the Gardiner Expressway: “The combination of the elevated portion of the Gardiner Expressway, Lake Shore Boulevard underneath it, and the rail corridor beside it has created a physical, visual, and psychological barrier to the Central Waterfront. It is a constant source of noise and air pollution, a hostile, dirty environment for thousands of people who walk under it daily, and a barrier to thousands of others who risk life and limb to get across or around it. The Gardiner/Lake Shore is not only a road; it is a structure. As it processes traffic, it stunts land use; meant to move us along, it limits our opportunities.” That commission recommended a mixed approach to the Gardiner, where some elevated sections remained, some were moved, and some were buried.

Speaking of burying the Gardiner…

Construction on the Gardiner Expressway, 1996. Photo by Boris Spremo. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0115149f.

Like clockwork, every few years a plan to bury or replace the freeway emerges. Each plan is initially greeted with relief that the waterfront will soon be rid of what many people perceive as an eyesore and barrier. Just as predictable is the backlash, which usually involves fears about runaway costs and traffic Armageddon during construction.

One of the first serious proposals to knock it down was in the fall of 1983, when Toronto Mayor Art Eggleton asked city staff to investigate burying the Gardiner. Eggleton was supported by Godfrey, who saw a golden opportunity for a new route through the not-yet-redeveloped railways lands to the north. Godfrey feared that “with all the bureaucracy and red tape involved in putting a roadway of that magnitude through, I really wonder whether we’ll all be alive to see it, even if all the money is available.”

The opportunity to use the railway lands soon evaporated, but other ideas abounded. City planning commissioner Stephen McLaughlin described to the Star three plans submitted to the city: “modest” ($25 million to demolish the Jarvis and York ramps and build a new exit at an extended Simcoe Street); “grand” (place the Gardiner in a trench or tunnel between Bathurst and Jarvis); and “visionary” (for $1 billion or so, re-route the Gardiner into a tunnel under Lake Ontario).

Sam Cass standing on the bridge over the Don Valley Parkway by Riverdale Park, 1971. Photo by Reg Innell. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0125807f.

Such plans were hooey to Sam Cass, Metro roads and traffic commissioner, and staunch defender of the Gardiner. Cass, who still promoted the completion of the Spadina Expressway in 1983, called the Gardiner “a beautiful structure that’s still doing what it was designed to do.” His contention that maintaining it wouldn’t cost much proved incorrect. Cass boasted that the Gardiner required no repair during its first decade-and-a-half and figured once a modestly priced five-year program to fix salt damage was completed, the elevated section wouldn’t require further repair for a quarter-century.

As annual repairs became a reality, calls for the Gardiner’s burial increased, especially as other cities contemplated demolishing their elevated highways. In a lengthy 1988 piece on why the Gardiner should come down, the Globe and Mail’s John Barber likened it to a Cadillac in a scrapyard. As chunks of concrete fell and its steel skeleton rusted, Barber declared “the highway that began life as a heroic symbol of the city’s progress is now just an overflowing traffic sewer.”

Toronto Star, January 20, 1988.

Among those Barber spoke with about alternative options was developer William Teron, whose company was covering over a section of the Boulevard Périphérique in Paris. Bringing his plan to municipal officials in 1990, Teron proposed an eight-lane Gardiner buried along the waterfront and a revamped, landscaped Lake Shore Boulevard. He promised to deliver the highway in less than three years and cover the $1 billion cost in exchange for development rights for housing and offices along the Gardiner’s former route, which Teron figured would recoup his costs. Naysayers included Metro traffic officials, who warned of cost overruns, overstatement of green space, massive traffic tie-ups during construction, and disruptions to TTC service.

Teron’s plan went nowhere, as have numerous other proposals since then (such as this one from 2013).

“Bumping the Humber Hump. Robert Balen works on 30 tonne steel beams for a new bridge over the Humber River, which will replace the westbound lanes of the notorious hump on the Gardiner Expressway.” Photo by Boris Spremo, 1998. Toronto Star Photo Archive, Toronto Public Library, tspa_0115144f.

Until 1998, one of the Gardiner’s distinguishing characteristics was the “Humber Hump.” Created by settling bridgework near the Humber River, it was a roller coaster ride that either thrilled or terrified. One of the best ways to experience the hump was riding near the back of a school bus, where the combination of position and speed would send you flying. During my university daze, I took a drama criticism class which included field trips into Toronto, and my classmates eagerly anticipated who’d hit their head on the roof when we rode over the hump.

But it wasn’t always fun. The hump witnessed several fatal accidents over the years, and going too fast could send your entire vehicle flying. After years of failing to remedy the settling, the bridge was replaced in 1998. The remnants were sent off to the Leslie Spit.

Demolition of Leslie Street ramp viewed from north side of detour, looking south-east. Photo by Peter MacCallum, January 20, 2001, City of Toronto Archives, Series 572, File 77, Item 4.

By the late 1990s, poor maintenance of the section east of the Don Valley Parkway prompted calls for a teardown. Opposition to the demolition came from two groups: film studios concerned about dust and noise that was factored into the final demo process; and local residents who worried about traffic spilling onto side streets and into the Beaches, even though drivers would be able to follow essentially the same route into the lakeside community. City councillor Tom Jakobek resisted demolition, devising several compromise plans that would have preserved part of the stump. “Cars are an important necessity in this society,” Jakobek noted in 1999. “Why would anyone want to eliminate road capacity anywhere, when it’s located in the middle of an industrial area and people use it?”

But Jakobek was in the minority: most attendees at public deputations wanted it to go away. City council approved its demolition in 1999. Only a few pillars remain, while land opened up for a bike path, big box shopping, and the TTC’s Leslie Barns facility.

Frederick G. Gardiner, 1961. City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 220, Series 65, File 175, Item 17.

“I’ve looked at this darn thing from one end to the other,” Frederick Gardiner observed in 1964, “and I can’t think of anything I would like to change.” Many Torontonians have and will continue to disagree. For years, the arguments over the Gardiner Expressway have boiled down to either maintaining it in some form to prevent excessive disruption to motorists, tear it down and redirect the traffic, or find creative uses to rehabilitate the existing structure.

The Bentway, as used for exhibits during Nuit Blanche, October 2019.

The latter has found favour in recent years, leading to artistic projects such as The Bentway. Housing and office towers have grown around the expressway in the core (but please, don’t throw your furniture toward the road!).

For as much as the Gardiner is maligned as a waste of money and an obstacle to the waterfront, I’ll admit it’s still thrilling to cruise into downtown at night along the elevated section, radio cranked to 11 to a song like Iggy Pop’s “The Passenger,” and soak in the lights and cityscape unfolding around you.

As Toronto Life concluded in 1993, “No matter what Toronto decides to do, it will be a prodigiously difficult project, politically and financially. It sounds as if it might require the skills of a politician as powerful and shrewd as, say, Fred Gardiner.”

Sources: Regeneration: Toronto’s Waterfront and the Sustainable City (Toronto: Royal Commission on the Future of the Toronto Waterfront, 1992); Toronto ’59 (Toronto: City of Toronto, 1959); Emerald City: Toronto Visited by John Bentley Mays (Toronto: Penguin, 1994); Unbuilt Toronto 2 by Mark Osbaldeston (Toronto: Dundurn, 2011); the May 4, 1954, May 17, 1956, December 8, 1956, March 23, 1957, July 30, 1957, August 8, 1958, August 11, 1958, December 3, 1959, February 6, 1962, October 20, 1988, May 12, 1999, and May 15, 1999 editions of the Globe and Mail; the September 14, 1949, July 8, 1953, January 2, 1954, May 3, 1954, July 2, 1957, November 21, 1973, September 30, 1983, September 13, 1989, April 24, 1990, May 18, 1999, April 28, 2000, May 6, 2000 and July 15, 2000 editions of the Toronto Star; and the September 1993 edition of Toronto Life.

Articles I’ve written that were incorporated into this post were originally published by The Grid on March 17, 2012 and July 24, 2012 and Torontoist on February 7, 2014.

2 thoughts on “The Saga of the Gardiner Expressway”