This installment of my “Retro T.O.” column for The Grid was originally published on June 12, 2012.

The City, November 4, 1979.

As Toronto settles into patio season, pause for a moment if you enjoy a fermented beverage with friends. As late as 2000, enjoying a summer drink in public was impossible in portions of The Junction, a legacy of the dedicated efforts of “Temperance Bill” Temple to keep the neighbourhood dry.

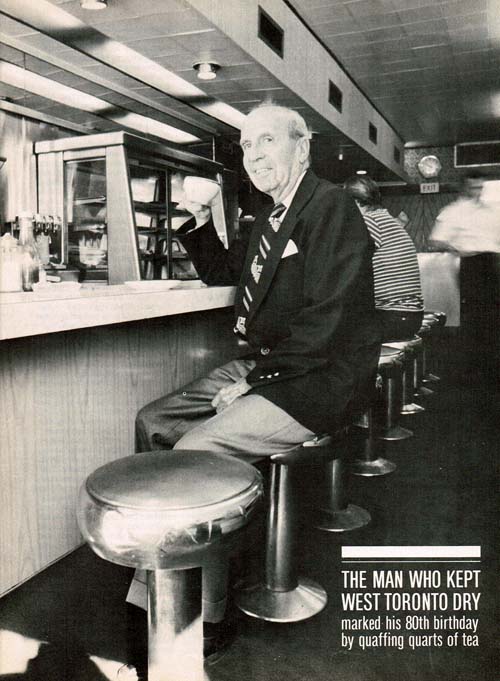

“He doesn’t look like a slayer of giants,” began William Stephenson’s profile of Temple for the Star’s The City supplement in 1979. “Not when he’s cruising the boulevards of the west end in his little red Pontiac. Nor while applying his special English to the balls at the Runnymede Lawn Bowling Club or felling the five-pins at the Plantation Bowlerama. Certainly not when he’s flirting with the nurses at St. Joseph’s Hospital each time he picks up the Meals-on-Wheels for delivery to Swansea’s shut-ins. On such occasions, the 5-foot-7, 130-pounder in the jaunty fedora and sport shirt looks like a successful politician, a Vic Tanny salesman, or perhaps a showbiz personality.”

Yet William Horace Temple slayed a few giants in his lifetime. The largest was Ontario Premier George Drew, who Temple, a faithful member of the CCF/NDP, defeated in the riding of High Park during the 1948 provincial election, despite having a budget one-fiftieth the size. Temple, who had lost by 400 votes in the previous election five years earlier, benefitted from fears about the repercussions of government legislation allowing cocktail lounges. Following Drew’s defeat, the provincial Tories used extreme caution in future attempts to loosen liquor laws.

At the time of The City article, Temple had celebrated his 80th birthday by downing quarts of tea. Though he once admitted to enjoying drinks to celebrate the end of World War I, Temple disdained anyone who imbibed. He believed the media was afraid to combat alcohol due to the power distillers held as advertisers, and claimed that all the negative aspects of American prohibition during the 1920s and 1930s was propaganda spread by liquor interests. “Booze enslaves, corrupts, destroys the moral fibre of a community,” Temple noted. “Battling the booze barons is the only honourable course for a citizen.”

Temple’s disdain for booze stemmed from his father, an abusive alcoholic train conductor. As a pilot in France during World War I, Temple frequently guided tipsy airmen to bed. As an RCAF duty officer during World War II, Temple infuriated his superiors by denying passes to senior officers he felt were too drunk to fly—“I had an uncomfortable war,” he later noted.

Keeping West Toronto alcohol-free was high among his pet projects. Its dry status dated back to 1904, when it was still an independent municipality. One of the conditions imposed when the area was annexed by Toronto in 1909 was that a two-stage vote (one for retail sale, one for restaurants) would be required to approve alcohol. The first major test came in the mid-1960s, when the owners of the Westway Hotel at Dundas and Heintzman organized a petition to allow alcohol sales. Temple, who headed the West Toronto Inter-church Temperance Federation (WTITF), delayed a vote by two years by proving many of the names on the petition were invalid. When the vote came in January 1966, the drys won. Temple’s forces won by an even larger margin in 1972, despite promises from a proposed Bloor Street bar to turns its proceeds over to Variety Village. Yet another vote in 1984 failed to sway the community.

Temple’s last hurrah came shortly after his death in April 1988. Smart money said that the temperance movement would collapse during a plebiscite that autumn without Temple’s determination and energy. “We did it for Bill,” proclaimed Derwyn Foley of WTITF when the drys won again. But it was one of the temperance side’s last victories. Throughout the 1990s, neighbourhoods within the dry area voted to allow alcohol. The last holdout voted 76 per cent in favour of allowing booze to be sold at restaurants in 2000 after dire predictions of increased crime and decay failed to materialize in the newly wet areas. As some proponents of alcohol sales predicted, an influx of businesses and eateries gradually flowed into The Junction.

If there’s an afterlife, it’s easy to imagine Temple’s reaction upon learning West Toronto had finally become wet. They would be the same words he yelled when he disrupted a Hiram Walker shareholders meeting in 1968 to find out if the distiller was funding politicians: “Sheep, nothing but sheep!”

Additional material from the November 4, 1979 edition of The City, the April 11, 1988 edition of the Globe and Mail, and the April 11, 1988 and November 15, 1988 editions of the Toronto Star.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

Apart from the image above, here is the full article on Temple from the November 4, 1979 edition of The City.

2 thoughts on ““Temperance Bill” Temple Keeps The Junction Dry”